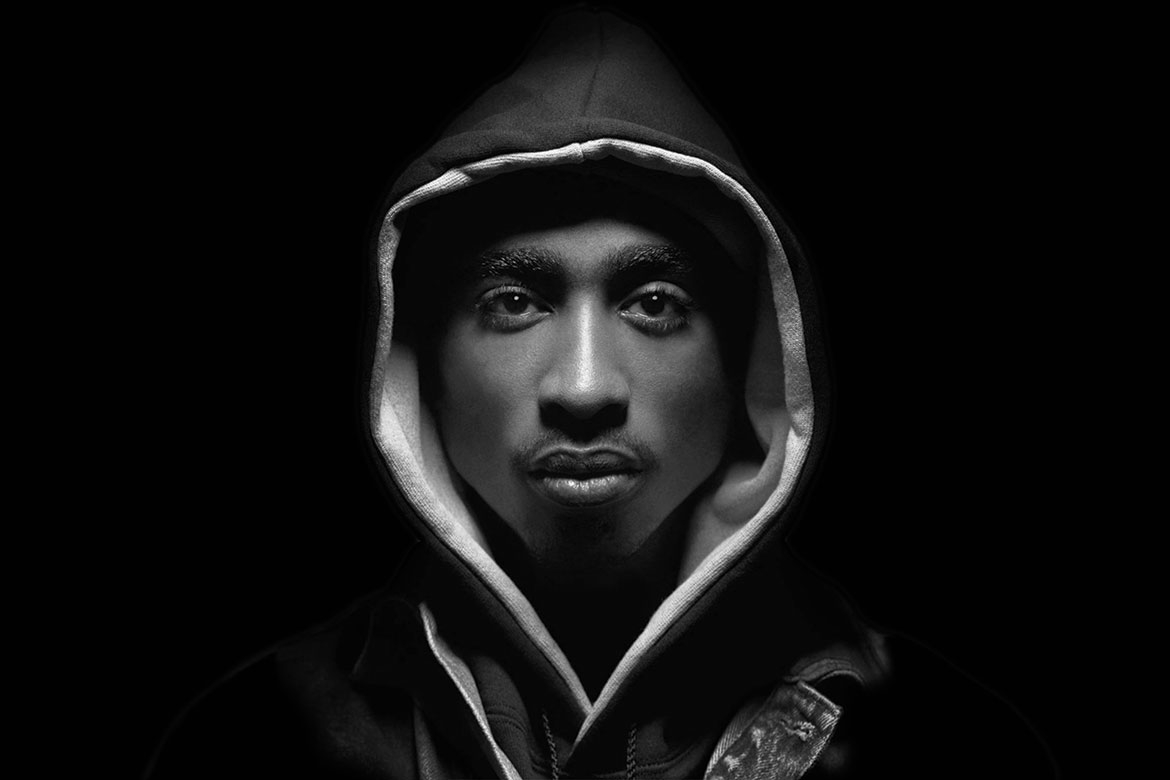

A New Take on Tupac from Director Allen Hughes

The FX docuseries Dear Mama reexamines legendary rapper Tupac Shakur through the lens of his relationship with his mother.

If you know Tupac Shakur's story, you might think Allen Hughes would be the last person to direct a documentary about the late rap legend.

It's true that Hughes and his twin brother, Albert, directed three of Tupac's early music videos, including the landmark Brenda's Got a Baby in 1992. But just two years later, Shakur was convicted of leading an assault on Hughes and sentenced to fifteen days in jail, fifteen days on a work crew and thirty months' probation.

The Hughes Brothers had cast the rapper in their 1993 film, Menace II Society, which would join the pantheon of pivotal 1990s dramas about young Black people in Los Angeles. But following conflicts during rehearsals, they fired him from the project. One year later, on the set of a music video, Shakur ordered his entourage to attack the director, witnesses said.

"The incident was terrifying," Hughes says, "because the [misconception] was that me and him got into a fight. It was ten guys who attacked me. ... I don't think I ever processed the trauma because I'm just one of those guys, when shit like that happens to me, I just pimp past it and keep moving. Despite that five-minute incident, we'd had about a year of intense friendship — that was way more profound than that."

Given that legendary bit of bad blood, how did Hughes wind up directing Dear Mama, a five-part docuseries for FX that tells the story of Shakur's life through the lens of values he learned from his mother, Afeni Shakur?

Hughes — who was nominated for two Emmys for The Defiant Ones, his 2017 HBO docuseries on the partnership between rap star Dr. Dre and producer–record executive Jimmy Iovine — says Shakur's estate asked him to take on the project when another filmmaker failed to pull it together. It took him a few days to decide whether to do it.

"Somebody from the family said during the meeting, 'To know Tupac is to love Tupac, and to know Tupac is to fight Tupac,'" Hughes recalls. "There's no such thing as being family or friend to him and not [occasionally] getting hostile ... and then back to love. I'm at peace with it."

After three days, Hughes went back to the family with a few conditions: it had to be a five-part series and it had to be as much about Afeni as Tupac. A member of the Black Panther Party, she'd instilled a strong sense of social justice and activism in her superstar son.

Focusing on Afeni, who died at sixty-nine in 2016, was a way of telling a new story that felt different from all the other examinations of Tupac's life, Hughes says. And the project was renamed: originally titled Outlaw, it became Dear Mama, after the 1995 hit the rapper wrote about his mother.

Afeni herself is heard in the opening voiceover of the music video: "When I was pregnant in jail, I thought I was gonna have a baby, and the baby would never be with me," she says. "But I was acquitted one month and three days before Tupac was born. I was real happy because I had a son."

The rap that follows is a pure expression of a son's love:

... You always was committed

A poor single mother on welfare, tell me how you did it

There's no way I can pay you back

But the plan is to show you that I understand

You are appreciated....

Dear Mama — the docuseries — opens with two of Tupac's relatives talking about an infamous incident from 1993, when the rapper shot two white men in Atlanta who he said were harassing a Black motorist. The men turned out to be undercover police officers. At the time, the police said the officers were confronting someone who'd nearly struck them with a car as they were crossing the street with their wives.

"That was the first time I realized [Tupac] was for real ... he's going to protect Black people," the rapper's cousin, Jamala Lesane, recounts. "That was how he was raised."

In further interviews, Afeni describes what she wanted — and didn't want — for her son. "I hate prison. I hate the sound of the door when it closes. ... I never wanted it to happen to my son," says his activist mother, who was arrested in 1969 and charged — along with other members of the Black Panther Party — with conspiracy to bomb police stations and other locations in New York. Though she and the others were acquitted after an eight-month trial, she spent time in jail, pregnant. Afeni represented herself through the proceedings.

"It was my responsibility to teach Tupac how to survive his reality," she says in the series.

The program — which will debut on April 21, with episodes dropping the next day on Hulu — digs into family history. It features interviews with Afeni's sister, Gloria Cox, as well as superstar friends of Tupac, including Mike Tyson and Snoop Dogg. Clips of a high- school-age Tupac reveal his outspoken nature.

In one snippet from 1988, he complains about having to study German. "When am I going to Germany?" he says. "I can't afford to pay my rent in America. We're not being taught to deal with the world as it is. We're being taught to live in this fantasyland."

Hughes spoke with emmy contributor Eric Deggans about the struggle to assemble Dear Mama. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You've said the Covid lockdown gave you a chance to recalibrate the docuseries ...

Yeah, it did. The first part of Covid was such an advantage for me, because we got to really process things. And the interviews were richer once we got back to it. Remember that first six months when everyone was appreciating life in a way that they hadn't before? It definitely affected the interviews. The disadvantage was working remotely. So, it was a double-edged sword. I didn't like not being in a room with the writers and editors and creating. That was difficult.

You may have believed the world would go back to how it was after a brief pause. But as we're learning now, it's not that easy.

Exactly. And the thing I did on my last docuseries, The Defiant Ones, I got to show ten minutes here, five minutes there to different groups and get a gauge of what people were understanding and not understanding. I lost that. I lost that connection to an audience. If that docuseries was like producing a rock album, this one was like a blues album. I'm playing for myself a little bit here. It ultimately worked out, but it was nerve-wracking.

It sounds like you've come to terms with Tupac's attack on you and maintained an admiration for his artistry and life.

This guy's a once-in-a-generation talent. There was no one like him. If he had lived, we would have gotten to the other side of it because we — me and my brother and Tupac — began our cinematic career together. He put us on the map just as much as we showed up for him, you know, visually. I think that's what touched me about the family and the estate coming to me. They said, "We're very disappointed in what's been out there on him in film and documentaries. And you're the only one that can bring this to a conclusion in a cinematic way." I took that to heart.

When he died — after being shot in Las Vegas in 1996 — Tupac was only twenty-five. But he was a huge star with a giant presence, which only expanded after his death. How did you tackle this sprawling story?

The challenge I took on was this: when you travel the world — whether it's Africa, Europe, Asia — you see his image in murals everywhere. The problem is, there's still confusion as to what he represents, outside of being this rebel-without-a-cause figure. That's where I said, if we can figure out what he truly stands for — the true meaning of his whole journey and his mother's journey — because he lost his way there at the end. ... But you've got to be careful about fucking with the mythology versus the reality. You got to be very thoughtful. And I like a challenge like that — I know I'm the man for the job.

As you worked, what did you learn about the Tupac mythology and where the reality began?

That's the question when it comes to this guy. I believe any great artist is 100 percent delusional. And we're lucky to receive a third of those delusions in the form of art. The other two-thirds is just stuff driving their friends and family crazy. I use the shooting of the two off-duty cops as the prism to deconstruct myth versus reality. We open with all the mythology of it, and as you unpack it over the five episodes you start to see all the other things that led to that happening.

When it comes to Tupac, the thing I bonded with him over was that, for him, the myth-making was a big deal. He was aware of the iconography, the image he was creating. And I think those lines got blurred out there somewhere in his journey. He didn't know where that reality ended and the myth-making started. And that's called being an artist.

The whole film is a meditation on what was real versus the mythical version. But it's all based in truth.

There was the image everyone reacts to — the tough guy with "Thug Life" tattooed on his torso — and the man behind that, who was something of a chameleon. One moment, he could be artistic and poetic and the next moment he could be combative and aggressive.

No doubt. You can project what you want onto Tupac. If you want to see a poet, you see a poet. If you want to see a fighter, you see a fighter. If you want to see love, you see love. Who else in our modern history can we project that much onto? Not even with Muhammad Ali or Malcolm X can you do that.

I want to ask you about the parallels with Kanye West. If you talk about somebody who has trouble distinguishing between myth-making and reality and somebody who was really influenced by his mother — seems like the two of them had a lot in common.

I want to be careful about how I say this. Kanye is forty-five years old. So, you can't say that all this stuff he's doing is still part of his youth or his progression as a man. The other thing I will distinguish — I don't know what he really stands for. I think that's a culture thing. That's what our culture has been reduced to.

When you look at celebrity, when you look at these stars, no one puts it on the line for what they believe in anymore. They just don't. Kanye versus Tupac — there are some very interesting similarities there. I do talk a lot about mental health in this film, too. And trauma versus Black trauma.

You changed the title of the project, from Outlaw to Dear Mama. What inspired that move?

I found out that Tupac had been making a documentary about himself and his mother with a music-video director friend of his [Gobi M. Rahimi]. And I got with this guy and picked up some of those pieces. I realized, "Oh, he was already wanting to do this." I saw what this all meant to him as it pertained to his mother. I realized this film was Tupac's love note to his mother. And it's also a love note to Black women in the struggle.

And I said, "Well, I was raised by a single feminist radical social- justice warrior mother myself. This docuseries is my love note to my mother." I wanted people to know. There is hip-hop, obviously, through this journey. But this is not just a hip-hop story. It's a bigger story.

With so many parts to his life and circumstances to reconcile, I would think finding a coherent throughline would be the biggest challenge.

The job for me, as a storyteller, was to reconcile all this madness we just [saw onscreen]. You've got to make sense of it. And that's the toughest thing I'm going to have to do. You have to bring order to disorder. You got to find melody in the chaos. At the end of episodes, you want viewers to say, "Okay, I'm getting a sense of what this means." Especially now in our culture, it is very important that we know what this means. When you're in good hands, you go, "Wow, this is very thoughtful. It's made me think. I didn't quite know that. I don't know if I agree with this. But now I have food for thought."

I found meaning in his death. He died and became this international, transcendent, iconic star. With Tupac and Afeni, you go, "Oh, look how great the symbol is. Look how great the original intent was, you know, fighting for human rights. Look at how smart these people were about this." And I wonder: maybe it wouldn't be able to get out to the world like this if he would have lived, you know?

Sometimes these guys become bigger in death.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #2, 2023, under the title, "His Mother's Son."