When Johnny Carson moved The Tonight Show from New York to Burbank on May 1,1972, comedians realized that if they wanted their big network break, they were going to have to head west, too.

New Yorkers started moving to California, and the West Coast Comedy Boom was born.

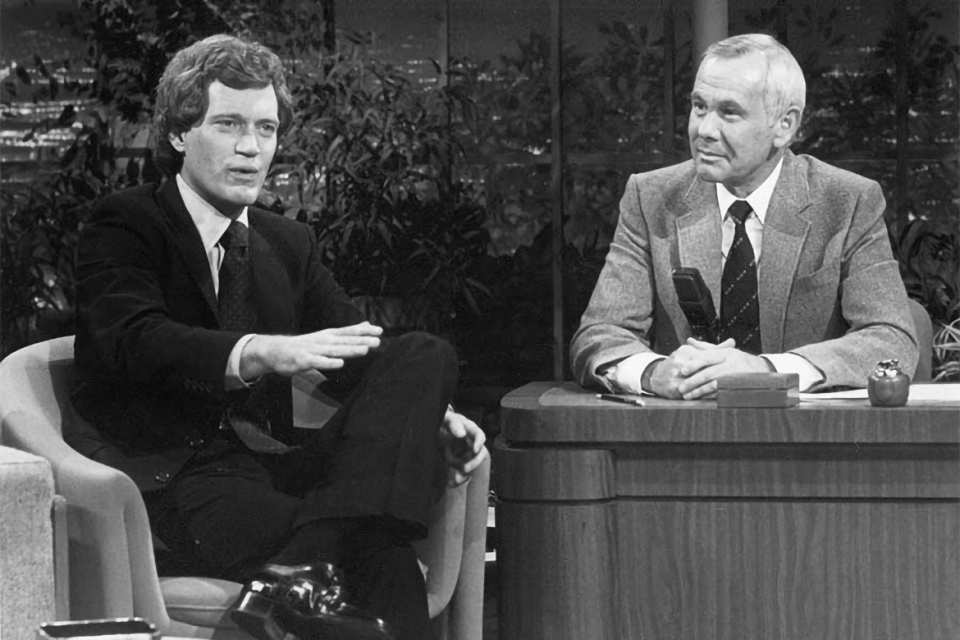

David Letterman was watching from Indiana. "In those days," he recalls, "if you wanted to go to California and become a comic or get involved in comedy writing, performing — whatever — the blueprint was laid out in front of you every night on The Tonight Show.

"They would have brand-new comedians — 'That was Steve Landesburg. You can see Steve Landesburg every night at the Comedy Store on Sunset Boulevard here in Hollywood.' Pretty soon you realized that was an instant connection: the Comedy Store."

Letterman was then doing sketch comedy as part of an Indiana trio that included Joyce DeWitt, best known today as Janet from Three's Company. Their biggest gig was a local bank's Christmas party, and Letterman warmed up the crowd. It was his first stab at stand-up, and it went poorly.

He also worked in regional radio and television, hosting late-night movies and doing the weather. His quiet ambition was vindicated when Betty White and her game show-hosting husband, Allen Ludden, came through Indianapolis.

They were promoting their syndicated radio program, which was carried on Letterman's station. They found him witty and charming and suggested he move to Hollywood.

Letterman arrived in L.A. in a beat-up old truck. He went on stage at a North Hollywood bar managed by Murray Langston, who as a stand-up would be known as the Unknown Comic.

"Langston had a little place in the Valley called the Showbiz," says comic Bill Kirchenbauer. "It was nowhere near show business. It was at the corner of Lankershim and Victory [in North Hollywood] and it was just a little hole in the wall. There was never much of a crowd."

Langston remembers Letterman being good from the start. "He lived one block away, on Oxnard, and was so damn good on stage, with a natural sarcastic ability."

As soon as Letterman went on stage at the Comedy Store — on the famed Sunset Strip — he was considered unique.

"Usually, when a new guy came in, the guys stood in the back and wouldn't pay attention," says comedian-musician Gary Mule Deer. "David went on stage in 1975.

"He had just been a weatherman and the first thing he said was something like, 'The management of WNAS would like to take this time to state they are diametrically opposed to the use of orphans as yardage markers at driving ranges.' Boy, did that get me. I went and sat in the front row."

Letterman had written six spec scripts in hopes of landing a sitcom job, but without a proper agent it was impossible to sell them. He decided stand-up was the best way to get attention.

"I started working at the Comedy Store," he says, "because it seemed like a more direct means of showing my work than printing up six truckloads of scripts and driving them all over town trying to get somebody to read them."

Letterman was a master at working crowds and much preferred the grind of hosting to a 10-minute set. "He never wanted to be the middle act or the headliner," says Mule Deer. "David always wanted to be the emcee."

He did the road, opening for singers like Lola Falana and Tony Orlando, who called Letterman the worst opening act he ever had. "I can't tell jokes very well," Letterman admits. "A good joke is such a well-constructed piece of writing, and writing a joke is just not natural for me."

To comedian Tom Dreesen, it was apparent Letterman had a different calling.

"He didn't enjoy stand-up, but he had an energy about him when he went on stage. David Letterman was a broadcaster being a stand-up comedian. He was destined to be a talk-show host. I went with him the first time he hosted The Tonight Show. When he walked out, I said to myself, 'This guy is home."'

Letterman got what seemed like a big break in late 1977 when former Comedy Store manager Rudy De Luca wrote a pilot with Christopher Guest, a satire of 60 Minutes called Peeping Times. Mel Brooks appeared in one segment, and the project was the first directing job for Barry Levinson.

De Luca explains how Letterman got cast: "This agent called me up and said, 'Would you hire this guy David Letterman? He's going to be very big.' I said, 'Bullshit. They all say that.'"

The famous Letterman tooth gap was a network concern. Letterman was told he would have to have his teeth fixed, but he fought for himself and won a compromise to wear dental inserts. "Which was fine," says Letterman, "except that when I wore them, I couldn't speak."

The network played Peeping Times for a test audience, and Letterman didn't do well. Levinson was told he would have to replace Letterman if the project were to move ahead as a series.

"It didn't go forward," Levinson recalls, "and that was the end of it. We had him under contract for $5,000 an episode if it turned into a series. He went on Johnny Carson a few months later, and NBC signed him to a $1 million holding deal. We had him for $5,000, and they didn't even want him in the show!"

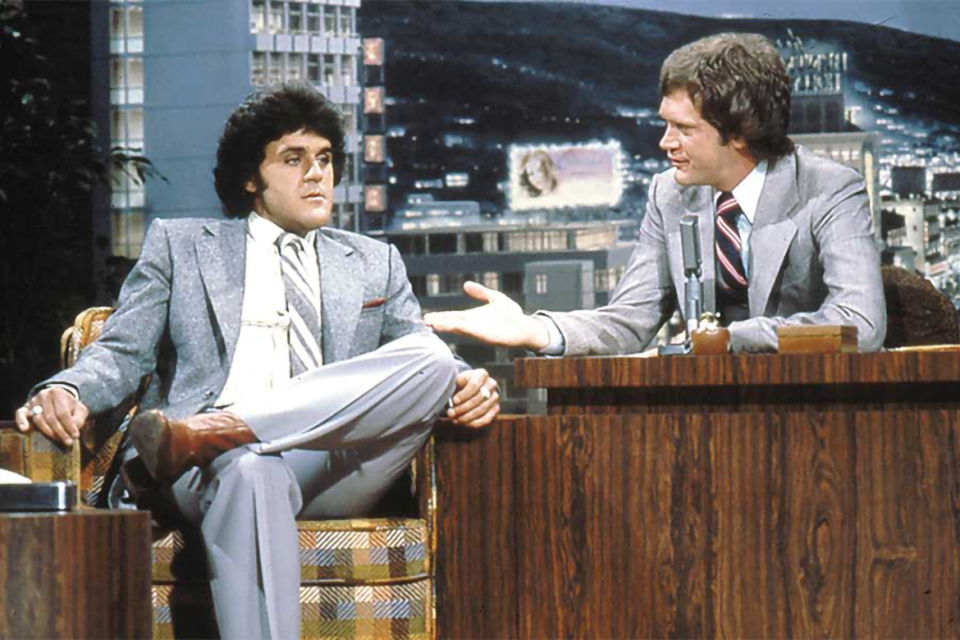

The night of that first Tonight Show appearance — November 26, 1978 — "was the most exciting thing in my career," Letterman says. "It took me a week to get over it." He returned a few weeks later, and by his third appearance he was hosting the show. No other comedian in Tonight Show history had ever received such a quick vote of confidence,

Letterman signed a holding deal with NBC in May 1979. By the time he got his own NBC morning show in February 1980, he had guest-hosted The Tonight Show 24 times.

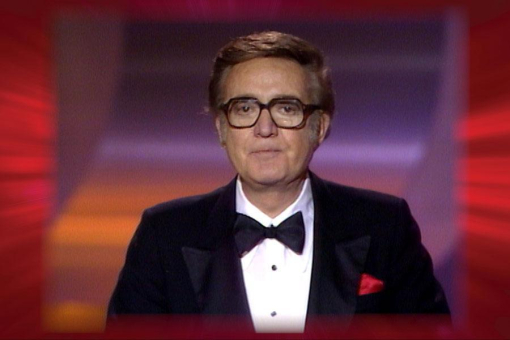

Former Tonight Show host Jack Paar predicted big things: "Of the newest personalities, David Letterman will unquestionably be a big star. He has an original style and winning manner that is lasting. He will go the distance."

NBC president Fred Silverman devised potential projects, none of which suited Letterman's sensibility. One was called Leave It to Dave. "The whole project was just a disaster," Letterman says. "I was supposed to sit on a throne, and the set was all pyramids. The walls were covered in shag carpet."

But Merrill Markoe, Letterman's writing partner [and sometime romantic partner], recalls that "the set was not even the worst idea to come down that particular pike. They wanted the guests to make their entrances by sliding down a chute."

Letterman resisted the network's many ideas, and when Silverman finally suggested a 90-minute daytime talk show, Letterman went along, saying, "It may not be the high side of glory, but it sounds like fun."

The network made a 26-week commitment. NBC president Brandon Tartikoff announced: "We think this program will upgrade and change the face of morning television." An unironic, cross-country campaign featured a photo of Letterman and the slogan: "A face every mother could love."

The David Letterman Show debuted at 10 a.m. on June 23, 1980, as a 90-minute program, the lead-in for Wheel of Fortune. The management team of Rollins, Joffe, Morra & Brezner was named producer and worked under the aegis of Letterman's brand-new company, Space Age Meat Productions.

There was an emphasis on conceptual comedy, improvised banter and offbeat comic guests like Steve Allen, Andy Kaufman and Steve Martin. Character actress Edie McClurg appeared as a sidekick of sorts, satirizing the daytime audience as "disgustingly pert, cheery and bouffant-brained homemakers dispensing such valuable household hints as how to refreshen a room gone stale from air freshener."

It was evident after a few weeks that daytime viewers were not digging it. Silverman cut the program down to an hour on August 4.

Some affiliates, like KYW in Philadelphia, were so dissatisfied that they arbritrarily cut the show down to 30 minutes on their own. Forty-nine out of a possible 215 affiliates failed to carry the program, Four major markets — Boston, Baltimore, Detroit and San Francisco — decided to drop the show altogether. It was consistently the lowest-rated program on daytime TV.

Markoe said their refusal to pander meant doom from the start. "The morning show was a delusion in the sense that we felt you could just do whatever comedy you wanted, anytime of day or night. And when the show started to fail, Dave was going crazy. It was not a happy time."

Acknowledging his poor ratings, Letterman slapped a portable TV on his desk and invited the audience to join him in watching the competition. Flipping channels, he settled on Dinah Shore's daytime talk show: "Dinah's makin' an omelet. Unbelievable!"

Remaining episodes of The David Letterman Show featured a sweepstakes in which viewers guessed the date of cancellation. October 24, 1980, was the winning answer, and Letterman was done with what he called "the best and worst experience of my life."

The show canceled, Letterman returned to guest-hosting, filling in for Johnny Carson for long stretches in December and January. NBC and Carson Productions signed Letterman to a new holding deal in February 1981, for $750,000 a year, while they tried to figure out what to do.

They considered using him as a replacement for Saturday Night Live reruns on the fourth Saturday of every month. They also proposed he follow Carson, but Tom Snyder, who held that time slot, was vehemently opposed. After the impasse was resolved, Snyder's contract was bought out and NBC announced that Letterman would get the time slot starting in 1982.

Letterman went back to stand-up. He played an anniversary show at the Los Angeles Improv in May 1981 in a lineup that included Billy Crystal, Larry David, Jay Leno, Fred Willard and Dr. Timothy Leary.

That summer he played the Ice House in Pasadena and picked up a Daytime Emmy for the defunct morning program. He hosted a comic-travelogue for HBO and guest-hosted The Tonight Show for the rest of the year.

Late Night with David Letterman premiered on February 1,1982, and he did his last-ever stand-up set on February 14, at Radio City Music Hall, as part of the ABC television special Night of 100 Stars.

Carson Productions dictated the procedure of Letterman's program. Nothing identifiable with The Tonight Show was allowed on Late Night: no guests like Buddy Hackett or Eydie Gorme, no brass instruments in the band and no reference to the monologue's being a monologue. For years Letterman's monologue was officially referred to as "opening remarks."

Letterman's staff members were actually pleased by the restrictions — it gave them the freedom to be different.

Since the new show was unable to acquire star power, Late Night with David Letterman booked underground heroes like Captain Beefheart, Harvey Pekar, Brother Theodore, John Waters and the cast of SCTV.

The marijuana smoke hovering above Paul Shaffer and the World's Most Dangerous Band added to the hipster cred. "You used to walk down that hallway on the sixth floor and you couldn't breathe," said producer Robert Morton. "It was the greatest fog ever."

Letterman's comedy was sometimes too weird for viewers and resulted in hostile reviews.

"There are people running amok through the boardrooms of America's third-place network these days, people who aren't playing with a full deck," wrote Bob Michaels in The Palm Beach Post.

"The ludicrous quinella NBC is banking on to become their superstars of the '80s is David Letterman and [actress-singer] Susan Anton. If someone set out to find a more no-talent pair than those two, they'd probably find them clutching a bottle of Thunderbird in some alley. To even consider Letterman in the same breath as Milton Berle or Jerry Lewis is an insult to comedy."

James Wolcott wrote a brutal assessment in New York magazine in 1983: "Late Night with David Letterman has become a creaking, facetious contrivance — a choo-choo forever wobbling off the tracks. If David Letterman is going to make it in the long haul, he's going to have to spend more time listening to grown-ups and less time staring at the shine on Paul Shaffer's head."

For comedy fans, however, and for comedians on the club circuit in particular, Late Night with David Letterman was essential viewing.

Exposure on the program boosted the ticket sales of established comedians like Robert Klein, Jay Leno, Richard Lewis and Jerry Seinfeld. It became a goal for club comedians Bill Hicks, Jonathan Katz, Sam Kinison, Norm Macdonald, Dennis Miller and Drake Sather, got enormous boosts from the program.

Jon Stewart's Kudos

In 1992, when Johnny Carson retired and NBC gave The Tonight Show to Jay Leno, Letterman left NBC to host his own 11:30 p.m. program, Late Show with David Letterman, for CBS. He retired from that program in May 2015. At the time Jon Stewart paid tribute to his friend and mentor on Comedy Central's The Daily Show. He said, in part:

"[Dave] was for the me and many comics of my generation an incredible epiphany of how a talk show or entertainment or a television show..." he trailed off, then resumed in wonder: "For God's sake, the man put a camera on a monkey! It seems so simple now. But back then it was mind-blowing,

"I watched that show since the early '80s and fell in love with the joy that they had and that they brought. There are so few people that can innovate that format — and then to have the kind of longevity.... To be an innovator with longevity is, I mean...the list is, I think, Dave!

"On a personal note, I had a show very similar to his that did not share the innovation part or certainly the longevity part and Dave was kind enough to come to our final broadcast and be the guest. He singlehandedly turned what was a funereal atmosphere into a celebration. He lifted all our spirits, He said to me — I'll never forget — 'Do not confuse cancellation with failure.'

"I thank him for all the amazing years of television and for that wonderful piece of advice. So cheers to you and Godspeed, young man."

-Eds.

Excerpted from The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels and the History of American Comedy and printed with permission from Grove Atlantic. Copyright © 2015 by Kliph Nesteroff.