Kim Coles was exhausted.

She'd had a standup gig in London and had flown to New York, then taken a red-eye into LAX so she could be there for the cast's first day of work in the spring of 1989.

After landing around three in the morning, she found a place to stay near the airport, slept for a few hours, showered, and then arrived at the Fox lot, on the corner of Wilton and Sunset. She was buzzing with nervous energy — and lack of sleep — as she met her castmates. "We were sizing each other up, looking to see who'd gotten the job," she says.

Many of the other cast members knew each other already, and not just the ones who were related. Damon Wayans and Jim Carrey were close friends. David Alan Grier had appeared in I'm Gonna Git You Sucka and Partners in Crime and was close with the Wayans siblings. Tommy Davidson had been a regular at the Comedy Act Theater and knew Keenen, Damon, Tj McGee, and Toney Riley.

Coles only knew Davidson, from doing standup gigs with him. Kelly Coffield and T'Keyah Crystal Keymáh, who were moving from Chicago, were relative outsiders, too. Coles and Coffield decided to sublet a house together in West Hollywood.

"We were all just excited to be with one another," says Coffield. "There hadn't been a show like this before. There was great camaraderie. We used to say, 'This must be what it was like to be on The Mickey Mouse Club.'"

The writing staff cranked out sketches every day. The ones Keenen liked got written up on notecards and tacked to the big bulletin board in Tamara Rawitt's office. The ones he didn't, went in the trash can. There was a feeling, at times, that the writing of sketches was an end in and of itself.

"I thought I'd written more than half of the show," says Rob Edwards, "then the next day you'd see the board again and everything I'd written was gone. I'd write a bunch of new stuff that would go up, then a couple days later, the board would shift."

Material that seemed funny at first would naturally grow stale with repeated exposure. Edwards says the smarter, more experienced sketch writers — "which I was not" — held their best material until the end of the writing process.

In a few weeks of writing, a mountain of sketches was generated. The pilot was slated to be an hour long, and Keenen wanted to produce at least an hour and a half of solid material to edit down. Extra sketches could always be banked for future shows. When the cast, producers, and writers got together to read through the initial cache of scripts, director Paul Miller, the SNL vet, was floored.

"I'd been through that with Saturday Night Live, but I had never been through anything like this," he says. "There must've been a hundred sketches read in one day. It was kind of numbing."

Interesting ideas got lost in the shuffle. Howard Kuperberg recalls a piece he wrote called "Picasso's Black Period," with Carrey as Picasso, that was discarded. Edwards wrote a sketch imagining the 1934 NAACP Image Awards. Trophies would be awarded to the likes of Stepin Fetchit and Hattie McDaniel, who played a series of infamous "mammy" roles, most famously in Gone with the Wind.

"The joke is the idiotically stereotypical characters that were accepted as mainstream entertainment back in the day," says Edwards. "I wrote it and everybody was high-fiving, but we wound up not shooting it. That broke my heart."

Some of the sketches that survived had a history that dated back years or even decades. Keenen and Damon had been playing some version of Wiz and Ice since they were teenagers. Kuperberg and Buddy Sheffield helped turn them into the first "Homeboy Shopping Network" sketch.

"Men on Film" dated back to Damon and Keenen's youthful masquerading as a gay couple around the West Village, and as movie-critic siblings Dickie and Donald Davis. Sandy Frank reimagined them as Blaine Edwards and Antoine Merriweather.

Initially, Damon and Keenen were set to play Blaine and Antoine. As Damon recalls it, Keenen gave his part away to Grier simply because he had too much other stuff to do, and Grier didn't.

Grier says he was originally slated to play the father in another sketch called "Hey Mon," about a family of Jamaican immigrants, but couldn't muster a passable Jamaican accent, so Damon — who had a Jamaican character in his arsenal — took that part, and Keenen gave Grier the part of Antoine.

Edwards recalls a related bit of horse-trading between Damon and Keenen. Both did pretty good Mike Tyson impressions, and either could've played the boxer in a sketch that imagined Tyson and then-wife Robin Givens on an episode of the dating show Love Connection. Both were also capable of playing Blaine in "Men on Film."

"Whoever did the film critic was going to get a lot of really creepy mail," says Edwards, "but whoever did Tyson was going to get punched in the face at a party when they least expected it. Tyson was notoriously thin-skinned and self-conscious about his voice. They kind of went rock-paper-scissors: Keenen got Tyson and Damon wound up doing the film critic."

Grier says the initial "Men on Film" script had fictional movie titles in it, but after read-throughs and rehearsals, he and Damon began improvising. "We started using real movies that had no gay connotation — like Top Gun, or whatever — which really upped the ante. The straighter the movie, the funnier it got that we would put this gay inference in it."

Blaine and Antoine were very much a product of a pre-politically correct era. Even back then, they raised the hackles of more than a few people. Don Bay, a gentlemanly lawyer who had been hired by Fox to run its Broadcast Standards and Practices Department, recalls meeting Keenen for the first time in the office of the VP of programming. Keenen outlined the show and mentioned "Men on Film."

"I was concerned about how gays would be treated since the subject was a sensitive one at that time, and I'd met with reps of the gay community before," says Bay. Fox Chairman Barry Diller was also uncomfortable with the sketch.

Back in 1989, Diller was already a legendary Hollywood executive, known as one of the smartest, toughest, most ambitious guys in the industry. He'd started in the mailroom at the William Morris Agency (now known as William Morris Endeavor), worked his way up to head of prime-time programming at ABC and eventually chairman of Paramount Pictures, where he reigned for a decade before being lured to Fox.

He was short and stocky, with a clean, shiny, bald head that only seemed to add to his intimidating mien. Diller read the "Men on Film" script, and according to Keenen, he raged to Fox president Peter Chernin about it.

"He was like, 'We can't do this — this might be going too far.'" Keenen recalls. "I said, 'Come to the rehearsal. Come see it, and if you have an issue with it after that, let's talk.'"

Diller came to the dress rehearsal in front of a live audience. "It sounded like somebody put a bomb in the building," Keenen says. "That's how big the laughs were. People were stomping their feet. No one had ever seen anything like this. Barry watched the whole thing and that was it." Diller was convinced.

As the dates for filming the pilot loomed, there was no real sense among the writers and cast which sketches were in and which were out.

Of those 100 or so that had been read through initially, many had been discarded, but many remained and new ones popped up all the time. "There would be six sketches up on the wall and we'd be prepping them with costumes and casting," says Edwards, "and the next day, six new sketches were up. Three days later, there would be three new sketches up. We never really knew what the rundown of the show would be."

This was a nice problem to have. There was so much good material that they were spoiled for choice. But the longer Keenen put off making a final call on the pilot's rundown, the more it created a logjam in the production cycle. People were waiting on him to do their jobs.

"We were about two weeks away from shooting and Keenen had not locked into a show yet," says producer Kevin Bright. "He kept the writers writing and didn't want to commit.

"Paul Miller and I were really concerned. We had to get scenery built. We thought maybe if we initiated a rundown based on the material we had, it would pin him down, get him to think about it and then work with us to commit to a show. So we did and showed it to him. He liked it and we were going to go with that."

But Bright had broken the rule Keenen had asked him to commit to when he first started: he wasn't supposed to be involved with creative decisions. "Tamara came into my office and told me Keenen was angry. I was out of my lane."

Miller says they ended up producing "many more sketches than we could ever use in one episode."

In addition to "The Homeboy Shopping Network," "Men on Film," and the Mike Tyson "Love Connection" sketch, the final rundown included Keymáh's "Blackworld" piece that she'd auditioned with, as well as a few short "Great Moments in Black History" bits that Edwards had proposed at his first meeting with Keenen. There was also a sketch with Keymáh hosting a female empowerment cable access show called "Go On, Girl."

Damon had a short commercial parody for the United Negro College Fund in which he played a malapropism-spouting prison inmate named Oswald Bates. The character was based on an impression Marlon Wayans used to do of a guy from the family's old neighborhood who'd gone to prison and returned spewing all sorts of half-cocked wisdom.

Damon had also written a funny Calvin Klein commercial parody called "Oppression." In addition, the final rundown included a sketch Sheffield and Kuperberg had penned, a commercial for a Broadway show featuring Sammy Davis Jr. — as played by Tommy Davidson — starring as South African freedom fighter Nelson Mandela, that was universally beloved among the cast and writing staff.

But arguably the sketch that both set the template and the bar for In Living Color was a Star Trek spoof called "The Wrath of Farrakhan."

In it, Damon plays the militant Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan aboard the Starship Enterprise. Farrakhan — as David Alan Grier's Spock helpfully tells Carrey's Captain Kirk (and viewers) — "is a former calypso singer who later became leader of a 20th-century African-American religious sect."

In the sketch, Farrakhan proclaims, "I've come to warn your crew of their enslavement on this vessel." Everywhere he looks on the Enterprise, he sees oppression. Uhura, played by Kim Wayans, is a glorified secretary who hasn't gotten a raise in 15 years. Grier's Spock is the crew's strongest and smartest, yet only second in command. Soon, Farrakhan has fomented an insurrection.

Executives at Fox weren't thrilled with it, figuring anything about Farrakhan was likely to stir up problems either from the Anti-Defamation League or the Nation of Islam itself. Probably both. As Rawitt recalls, "Everybody at Fox said, 'Nobody knows who Louis Farrakhan is! Nobody is going to care!' The point is, you let us create a show for black culture. Everyone in black culture knows who Farrakhan is."

Keenen was steering the show without a road map. He was making people nervous. Even the show's own writers and producers didn't always agree with him.

"Most of the time, the joke is on the media, on white people, on white fear," says Edwards. "'Homeboy Shopping Network' divided the staff. That one seemed to come from a different point of view, where the people being made fun of were poor black people."

It was certainly possible to see Wiz and Ice as just a new version of the same Stepin Fetchit stereotypes Edwards had skewered in his 1934 NAACP Image Awards sketch. "For us black writers, it seemed like it was punching down, which you're not supposed to do in comedy. It seemed like making fun of people who didn't need to be made fun of."

The same, he says, applied to "Men on Film." In both cases, though, political righteousness proved less important than comedic effectiveness. "Sometimes when you take something to the stage and it gets a laugh, the laugh wins out," he says. "Ultimately, we lost the battle."

It was the first battle in a war that would last as long as the show itself.

Keenen had to be convinced to host In Living Color. He had no real interest in getting onstage to welcome the audience and introduce everyone.

But there was a pervading feeling that not only would Keenen's presence give the show a sense of cohesion — as opposed to being a bunch of disconnected sketches — Fox felt it would make it clear that the creative force behind these racially charged sketches was a black man.

For the pilot, the plan was to run through the show on two consecutive nights, in front of two different audiences. That way, they'd have two takes of every sketch. If necessary, they could do pickups — filming extra bits that didn't work in the original takes — after the audience left.

The first night, after Tommy Davidson warmed up the crowd with some standup, Keenen opened the show by introducing the Fly Girls and the show's DJ, a guy known as DJ Daddy Mack, who was dressed in a tall black top hat with a big Africa emblem on the front of it. Keenen then wandered backstage to introduce the cast and crew.

"I'll tell you what I'm most proud of," he says to the camera. "Unlike other shows, I've got nothing but qualified black people backstage making decisions." With that, he opens the writers' room door and a bunch of white writers scurry out. He claims they're the cleaning staff. He introduces a black cleaning lady as the head writer.

"Now I'm going to introduce you to our cast," he continues. "We went nationwide to find the most talented people in the country." He then introduces "Damon Wayans," "Kim Wayans," "Tj Wayans," "Toney Wayans," "Tommy Wayans," and so on.

Next, Keenen boasts about how integrated the show is.

"People of all races working together as one big happy family," he says as he opens a door marked, "White Cast Members Only." Behind it are Carrey and Coffield. He's shining shoes. She's ironing. They're both grinning broadly and singing, "Camp Town Ladies." Keenen smiles. "Oh, those people. Always singing, always happy."

It was a whip-smart, playfully barbed reversal of the racial dynamics that had ruled television since the medium's invention.

Back in front of the audience, Keenen is confronted by the network's "censors," who make it clear that most of what Keenen had been planning for the pilot is unacceptable. Keenen makes a show of defiance. "I refuse to be silenced," he tells the audience. "We had this really great sketch that I wanted to do for you anyway. It started off like this: See, Ronald Reagan in 1975…"

At this point, Keenen is rendered inaudible by the sound of a loud, long beep. He continues ranting, but can't be heard. The bit is a direct homage to — or, less charitably, a rip-off of — a routine from The Richard Pryor Show more than a decade earlier.

The first set-piece is the "Love Connection" sketch with Coles as a gold-digging Robin Givens, Keenen as Tyson and Carrey as the show's host, Chuck Woolery.

Later in the show, Davidson does his Sammy Davis Jr. as Mandela. Dressed in a Star of David necklace, pinkie rings and an African dashiki, Davidson turns the song "Candy Man" into "Mandy Man": " Who can take apartheid/ Turn it inside out/Show those Afrikaans what this freedom gig's about?/The Mandy Man can… The Mandy Man can but they locked me in the can and threw the key away ."

Coffield pops up twice as part of a recurring meta-routine, playing an uptight white woman writing a letter to the network to complain about the show.

"I realize in the past blacks have suffered some… unpleasantness," she dictates aloud, "with that whole slavery thing and all, and that some resentment may be justified. Maybe it would help you if I shared with you a little secret I know. Just take a deep breath and say to yourselves, 'Sticks and stones may break my bones, but hundreds of years of oppression may never harm me.'"

There are other short interludes. The two "Great Moments in Black History" sketches — one with Toney Riley as a lazy gas station attendant who "invents" self-serve gas stations by telling a customer to "Get it your damn self!"; the other with Jeff Joseph as Slick Johnson, the first black man on the moon, left behind by the crew (and subsequently erased from history) when the mission needs to jettison weight for the return to Earth — are in and out in about a minute.

A spoof of the show 227, called "Too-Too Ethnic," is less than 30 seconds. Keenen's instincts seemed to be spot-on. For "The Homeboy Shopping Network," a truck full of electronics and other "stolen" goods was driven onto the soundstage as a prop.

"When we did a rehearsal," says Bright, "there was one of those smaller satellite dishes in the truck and Keenen said, 'No, I want one of those big, giant satellite dishes.'" Bright wasn't sure it was worth the trouble.

"It's going to be awkward and hard to get that out of the truck," he told Keenen.

"No, man, I want the big one," Keenen insisted.

For the pilot taping, Bright got a huge dish with the words "Property of NASA" on it. Bright laughs. "Keenen was right. I remember him lugging that satellite dish out of the truck the first time. The big one was so much funnier."

As the sketch was being filmed, Paul Miller was in the control booth. The technical staff was laughing uncontrollably. The show's lighting director, an older white man, turned to Miller, a little sheepishly.

"I can't believe we're doing this," he said about the "Homeboy" sketch. "Is this okay to say?"

Miller nodded. "Yeah, because Keenen is saying it. It wouldn't be okay for you or me to say, but it's okay for Keenen."

The pilot's tone was consistently cutting without ever falling into outright nastiness. It had a clear point of view. Edwards recalls that it took the crowd a sketch or two to get the rhythm of the show. Then, he says, the place went nuts.

"Black audiences don't just laugh at stuff, we stomp our feet, we high-five," he says. "People were literally running up and down the aisles during the taping, high-fiving each other. One of the executives turned to me and said, 'Did you pay these guys to do that?'"

The second show, the next night, went just as well, if not better.

"I've never done a show that felt that way in front of an audience," says Bright, who later became the co-creator of Friends. "At Friends, I'd never seen a first taping of anything where the audience was that crazy. They were on fire, both audiences. It was like the show had been on forever."

After the second show, Bright encountered Keenen backstage. "Keenen wasn't an emotional touchy-feely guy, and when we finished the second show, he physically lifted me up in the air and gave me this big bear hug. It can't go better than that."

Kim Wayans, who, in addition to her part in "The Wrath of Farrakhan," also appeared in "Go On, Girl" and "Too-Too Ethnic," says the energy in the air was palpable. "You could feel something new, exciting and fresh happening," she says. "After the pilot, we all knew we had something special."

Keenen walked toward the conference room at Fox's Executive Office Building not knowing what to expect. The pilot had gone great, but since then he'd heard a lot of nothing from the network. There was research to be done. They were testing it. Today's meeting was with something called "The Research Group." Both Barry Diller and Peter Chernin were going to be there, too.

Keenen liked Diller and Chernin, and he thought they liked the show. Yet months had gone by since the pilot with no word of whether it would get ordered as a series. The cast members were under holding deals but had scattered to the wind. Damon, Jim and Tommy were doing standup. Kim Wayans got a temp job as a secretary at an oil company in downtown Los Angeles, Coffield and Coles went to New York.

All would occasionally call Keenen to check in. He wished he had more to tell them. Some began to assume the worst. A recent call from Coffield was typical.

"I just got offered a play in New York," she told him.

"What are you asking?"

"I'm asking if you have any idea if this thing's going to get picked up."

"No idea," he told her. "Just do the play."

Keenen hoped this meeting would start to clear things up, though he wasn't expecting much. When he sat down, he saw who The Research Group was: five stiff-looking white guys in dark suits and starched shirts. "I felt like I was sitting with the NSA," he says. "Not a funny bone in their bodies."

They told him about the work they'd been doing. They'd been showing the pilot to focus groups and asking people how it made them feel.

"Wow," Keenen said, a little taken aback. "That's deep."

"Tell me what your vision is for the show," said one of the suits.

Keenen told them it was going to be fresh and new. "It's going to be revolutionary!" he said excitedly.

There was silence in the room. Keenen quickly divined that to these five men in dark suits, "revolutionary" wasn't a good thing. It conjured visions of Black Panthers and Molotov cocktails. Of Malcolm X's demand for freedom, justice, and equality "by any means necessary." He tried to assuage their fears.

"No, not take-over-the-world revolutionary. Revolutionary in terms of funny."

The room exhaled. The Research Group seemed satisfied. He'd never seen any of the men before that day, and once the meeting was over, he never saw any of them again.

The meeting was a pretty good indicator of what went on for about nine months following the making of the pilot. Fox said they wanted edgy programming, but now that they had it in their hands, they weren't sure what to do with it. It's not that they didn't like the show. They just didn't know how everyone else would react to it.

"It was really, really funny, but people were nervous to put the pilot on," says Joe Davola, the V.P. of development who oversaw the show. "You're talking about a Fox network that's run by white executives. Everybody was oversensitive. We didn't want to offend too many people."

Diller, in particular, was very worried about being perceived as racist. The solution, Diller and others at Fox thought, was to get buy-in from prominent African–American groups.

The pilot was screened for members of the NAACP and the Urban League. Fox reached out to C. Delores Tucker, a civil rights activist who later became a prominent crusader against rap music, and Alvin Poussaint, another activist who was a consultant on The Cosby Show. Meetings were arranged with various interest groups. Keenen was appalled and refused to attend.

"A couple of groups wanted to be brought on as consultants, which Keenen thought was a bribe," says manager Eric Gold. The quid pro quo was unstated but understood: if Fox paid a consulting fee, the groups wouldn't make a fuss. "Keenen didn't like it and wouldn't even meet with them."

As one story goes, at one point the NAACP tried to pressure Keenen by asking how many black writers and producers he'd hired. He challenged them to send over a list of all the black writers and producers they knew. They didn't have any such list, and that was the end of that.

Keenen found the idea of checking his work with other black people galling. Did Woody Allen need a thumbs-up from the Anti-Defamation League before he released a film? Did studios clear every John Hughes movie with suburban white people?

"At one point, Fox brought this old black man that they wanted to hire as a consultant to the show," says Keenen. "They told me how he'd marched with Dr. King and had a lump on the side of his head from when he got beat up. I said, 'I respect all he has done, but if he ain't got no jokes, I don't need him. He's no blacker than me. I don't need him to validate me.'"

Gold was impressed. "He stood up and said, 'I'm not doing it that way.' Can you imagine this? Where did this guy learn this kind of backbone?"

Fox had reasons to be optimistic about In Living Color. All around, the seeds planted in the earlier parts of the decade were beginning to flower. Arsenio's talk show was becoming a cultural phenomenon. The Cosby Show was the top-rated show on television. Its spinoff, A Different World, was also a hit.

Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing had been nominated for the Palme d'Or at Cannes. Harlem Nights, Eddie Murphy's directorial debut, was released in late 1989 to middling reviews but strong box office returns, eventually earning nearly $100 million. And in January 1990, Fox spun off a strange little cartoon family sitcom called The Simpsons from The Tracey Ullman Show. The early reviews were glowing.

Still, it wasn't clear what might prod the network's top brass into making a decision about ILC. Time dragged on. Nearly nine months had passed since they turned in the pilot and still no word. Tamara Rawitt tried to force their hand. She slipped videotape copies of the pilot to everyone she knew in the industry. The tapes got passed around. Davola gave out copies, too.

Martha Frankel, a writer for Details magazine, went to dinner one night in Los Angeles with Rawitt and another friend. At dinner, Rawitt bemoaned the situation. She'd helped build this show from the ground up, they'd made this amazing pilot, everyone loved it, but Fox wouldn't put it on.

Rawitt handed her a videotape, and when Frankel got back to her hotel, she popped it in the VCR. "It was truly the funniest thing I'd ever seen," Frankel says.

The following night, she invited several friends to her room and showed it to them. "We were screaming with laughter." She called Rawitt and asked if she could write a story about the pilot. Rawitt encouraged her to. Frankel wrote a page-long rave about the pilot, asking pointedly why Fox was sitting on it. When the issue hit newsstands, Rawitt ripped the article out and sent it to Diller's office.

"I said, 'Now, what are you afraid of?' The next day we got a pickup for eight episodes."

Changes had to be made before the first episode aired. An hour of sketches every week was too much. Too much for the audience and too much for the creators. ILC was going to work better as a half-hour show, something Rawitt says she figured from the outset. Leave the audience wanting more.

Much to the chagrin of Chris Albrecht and Carmi Zlotnik, HBO — which produced the pilot — didn't have the stomach to hang in there for the series. This wasn't a reflection of the controversies the show might engender; it was a money issue.

Michael Fuchs, the head of HBO, wasn't prepared to deficit-finance ILC — essentially, lose money in the short run in the hopes of turning a big profit if and when the series went into syndication. The project got passed to Fox's own studio arm, Twentieth Television. And with Albrecht and Zlotnik gone, the producer they'd brought in for the pilot, Kevin Bright, was out, too.

He'd already run afoul of Keenen by creating the initial rundown for the pilot, and seemed to be straining against the mandate to keep his nose out of the creative side of the show. Davola says that there was also a feeling that he was too close to the production people on their way out. According to Gold, though, there was a more personal reason for his dismissal: He'd had Shawn Wayan's car towed.

"Kevin Bright ended up getting fired off the show for the worst possible reason," says Gold. Shawn was working as a production assistant on the pilot and, by his own admission, had very little idea how a television production worked.

Among the things he didn't know was where to park his car. "I remember not understanding that I was parking in the producer's parking spot," Shawn says. "I had no idea. I was just looking at it like, 'Keenen parks here and Damon parks here, so I'm gonna park here.'"

But to some, this was a sign of unearned and unwelcome entitlement on the part of the show creator's little brother. It crystalized a lot of anxieties about Keenen possibly playing favorites with his family members. At any rate, Bright had his car towed. The incident was the culmination of several things that put some distance between Bright and the show. "It was after a lot of 'Maybe Kevin doesn't get us,'" says Gold.

Bright was disappointed to be out, but things worked out okay for him. He had already started developing the show Dream On, with Marta Kauffman and David Crane, for HBO, which eventually ran for six seasons. In 1993 he formed Bright/Kauffman/Crane Productions, and produced a sitcom about six young New Yorkers called Friends, which became one of the most popular sitcoms in television history.

The ILC writing staff also went through a shakeup. After the long lag time between pilot and the pickup, only Sheffield and Frank returned for the series. Rawitt had to re-staff almost completely.

Her initial haul netted two more ex–David Letterman writers, Matt Wickline and Joe Toplyn; the writing team of Mimi Friedman and Jeanette Collins, who'd never worked in television before; and two seasoned black standups, Franklyn Ajaye and Barry "Berry" Douglas.

With the show running at 30 minutes instead of an hour, the cast needed trimming. Jeff Joseph left with Bright to work on Dream On. Toney Riley and Tj McGee were deemed surplus to requirements.

The Fly Girls underwent personnel changes, too. A.J. Johnson was offered a part in House Party, a low-budget film that a pair of brothers, Reggie and Warrington Hudlin, were making with rappers Kid 'n Play. Keenen told her she had to make a choice: the show or the movie. Johnson wanted to do both.

"I can choreograph a 30-second dance number in my sleep," she told him. It was a sticky situation made slightly stickier by the fact that Johnson and Keenen were, in her words, "kind of dating." "I remember us arguing about it," she says. "Like, 'Why are you holding me back from going away to do a movie over a 30-second dance bumper?' We had a hard time in our friendship over that."

Ultimately, a choreographer named Carla Earle was hired. The decision was made to cast a wider net for dancers, so Earle arranged new auditions and saw more than 2,000 of them during a three-day stretch.

Deidre Lang, a dancer from the pilot, says there was a clear imperative with the new auditions. On the pilot, she explains, all four dancers were African-American. "Once the show got picked up, they were like, 'We need this to be more of a melting pot. We need to have each race.'"

One of the dancers who auditioned was a striking young Asian-American named Carrie Ann Inaba. It was one of Inaba's first casting calls, and she fretted over what to wear. "I chose this super-lacy bra I bought from this really expensive lingerie store, black leggings, motorcycle boots and a black jacket." Keenen later told her that the outfit got her the gig.

"He was like, 'Your outfit was so strange, but you looked like you thought it was the best,'" she says. "'You walked in with so much confidence, I pretty much gave you the job the moment I saw you.'"

Along with Inaba, two other women were hired from the auditions: Michelle Whitney- Morrison, a raven-haired beauty who'd been on the show Fame and had a minor role in School Daze, and a tall blonde named Cari French. Lang stayed on from the pilot, as did Lisa Marie Todd.

The final troupe fit the United Colors of Benetton ideal. "We had an Asian girl, a dark-skinned sister, a light-skinned sister, an Italian girl and a white girl," says Earle.

The DJ from the pilot, DJ Daddy Mack, was replaced for the series with SW1, better known as Shawn Wayans. Keenen knew Shawn wanted to be a part of the show, but also knew that as a writer, standup or actor, he simply wasn't ready.

Bringing him in as the DJ, introducing him to audiences while he worked on his comedy chops, made sense, though Shawn maintains that wasn't the original impetus for the change. "They wanted someone with a bit more swag," Shawn says. "I had a little swag, so one of the producers suggested me."

The not particularly well-kept secret was that Shawn, unlike the man he replaced, wasn't a real DJ. Up in the booth at ILC, his job was to merely act like a DJ. None of his equipment was connected to anything. "I'd listen to the tracks and make sure I was on cue when the camera cut to me, to look like I was mixing," he admits.

As Keenen puts it, "It didn't matter whether he was a DJ or not, because it wasn't live. He was a cute kid, and he wanted to be around his brothers while he was working on his standup. So I put him up there."

Perhaps Shawn's biggest musical contribution was helping recruit rapper Heavy D to do the show's theme song. As Keenen recalls, "Heavy grew up with my cousin in Mount Vernon, and he and Shawn were friends. So I told him what the show was, and he went off and put it together."

Heavy D, who died in 2011, was already a star in hip-hop, and his association with the show helped build its credibility. For Keenen, the song, with its energetic verses, rhythmic turntable scratches and singsong-y chorus — " You can do what you want to/In Living Color " — was "perfect" for what he was trying to get across. "I couldn't ask for anything more."

In trimming the show to a half hour, cuts needed to be made to the pilot. Sammy Davis Jr. was undergoing a battle with throat cancer — one that he'd eventually succumb to in May 1990 — so the decision was made to shelve Tommy Davidson's Sammy-as-Mandela sketch.

At the time, it was perhaps understandable, though with the release of Mandela from prison in South Africa that February, a counterargument could be made that the sketch would never had been timelier. The fact that it was permanently shelved leaves Davidson smarting all these years later.

"I don't know why they didn't air it, because somebody being sick is not enough to me," he says. Far from being a takedown of Sammy, the sketch "was an ode to him. Personally it would've established me as one of the frontrunners of the show." Instead, Davidson was barely in the show's first episode. Some have suggested Keenen was trying to ensure Damon would be the breakout star of the ensemble.

Other choices had to be made about episode one, and everyone, it seemed, had an opinion, including Barry Diller and Peter Chernin.

If Diller was known as bullish and intimidating, Chernin was prized for his bedside manner. Chernin had worked in publishing before moving over to television at Showtime, where, like Albrecht at HBO, he pushed the network toward original programming. By the time he came to Fox in 1989, he was an executive known for building bridges, not burning them. He was the one you sent in to ease your show creator off a ledge.

Chernin had asked Joe Davola to talk to Keenen about toning down the first episode, but Davola balked. Davola had spent a lot of time building trust with Keenen and didn't want to ruin their relationship. Besides, he didn't want to be the messenger for a message he didn't agree with. About a week before ILC was set to debut, Chernin went to see Keenen himself.

"Peter said, 'We want to make some changes to the pilot,'" Keenen recalls. "'We want to take out "The Homeboy Shopping Network," "Men on Film," and "The Wrath of Farrakhan," come in with some tamer stuff and slowly build this audience. Then we can really push the envelope.'"

It wasn't a totally unreasonable suggestion. Why scare away potential viewers right out of the gate? Why not warm them up a little, build a relationship with them, so they'll be open to the more radical sketches later?

Fox wasn't in an unassailable position. The network was limping along, still only broadcasting three nights a week, with a couple of modest hits to its name. Upsetting viewers and advertisers wasn't in its best interest.

Chernin and Diller weren't big, bad, clueless executives stomping out creativity they didn't understand. They liked the show. They liked Keenen. They wanted to help him succeed. Chernin wasn't trying to sand down the show's jagged points, just rearrange them a little.

Keenen wasn't interested: "I said to him, 'Peter, I wanna kick the door in, guns blazing. Whatever happens, happens. If we fail, we fail big. If we win, we win big. I don't wanna spoon-feed the audience. I want them to know exactly what time it is. I'm willing to take that risk. Whatever heat comes, send it my way.'"

It was an impassioned defense, and Chernin took it in for a minute. He told Keenen he'd talk to Diller and get back to him. It was a high-stakes staring contest. Fox blinked first.

"They were like, 'Okaaaay,'" says Keenen, letting out a theatrical sigh. "'If you take the heat and you're okay that this could be the worst thing that ever happened in the history of television, we'll support you.'"

With that less-than-unqualified vote of confidence, In Living Color debuted on April 15, 1990.

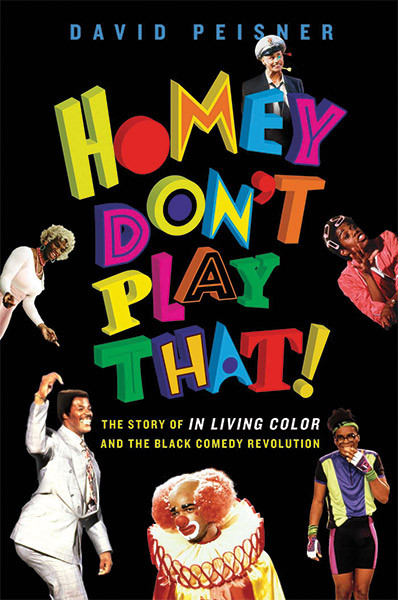

Excerpted with permission from Homey Don't Play That! The Story of In Living Color and the Black Comedy Revolution, copyright ©2018, David Peisner; 37 Ink/Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 8, 2019