In the highly popular CBS series Touched by an Angel, actress and singer Della Reese played a heavenly supervisor to other angels sent to help people through personal crises. It was a late-career boost for Reese, who was born Deloreese Early in Detroit, Michigan. The multi-talented performer was in her sixties when she was cast in the top-rated show, which ran from 1994 to 2003.

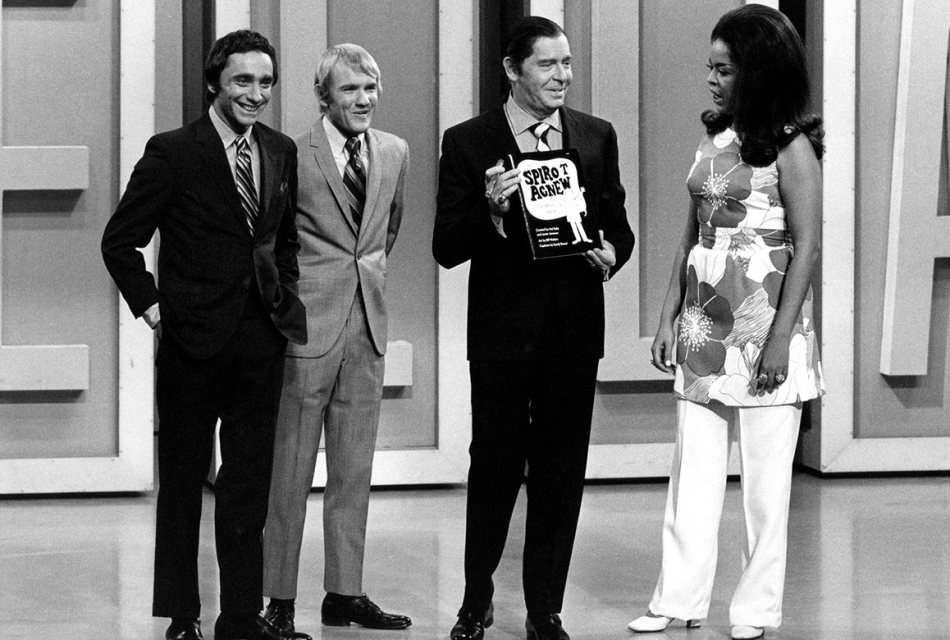

Reese started out as a gospel singer, then specialized in performing jazz standards. She had hit songs in the '50s and a jazz nightclub act in the '60s. She then made the transition to television acting and hosting, starting with her first television role in The Mod Squad in 1968. From 1969 to 1970 she hosted The Della Reese Show, becoming the first Black woman to have her own national talk/variety show. Though that program lasted only one season, she continued to be a presence in live television as a guest host for Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show.

Religious faith was a constant in Reese's life, and she became an ordained minister in the '80s. Her role as angel Tess in Touched by an Angel, which she performed with an irreverent streak, was in line with her beliefs and garnered her Emmy nominations in 1997 and 1998 in the category of outstanding supporting actress in a drama series.

Reese died in November 2017, leaving three sons and her husband, Franklin Lett. She was predeceased by her daughter. She was interviewed in June 2008 by Beth Cochran for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire interview can be screened at TelevisionAcademy.com/ Interviews

Q: When you were young did you have a sense of what you wanted to be when you grew up?

A: I always was what I wanted to be. My mother says that when I was born and they slapped me, I didn't cough, I began to sing and I never stopped.

Q: When did you land your first recording contract?

A: I was working at the Flame Show Bar [in Detroit], and the manager really liked what I was doing, so he had a friend in New York, Lee Magid, come to Detroit and see me. And he said, "If you ever happen to be in New York, call me." I went home that night, packed my bag and went to New York and called him.

Q: In the 1960s, you made the rounds of the talk/variety show circuit. How did you meet Merv Griffin?

A: I was working in New York, and Merv was doing a radio show. At that time, Count Basie had written a song that had a really marvelous groove to it, and Merv began to sing the weather report to this song. I began to sing the weather report, too, and we had a marvelous time.

Then he got his television show. At that time, if you had a hit record, if you were Black — you could sing on the show, but nobody ever invited you over to sit down and talk. They would open the curtains, you would sing, they would close the curtains and the master of ceremonies would move on.

Well, having done this song of the weather report with Merv, and having spent time with him at a fundraiser we did, he knew that I could carry on a conversation, so he broke the barrier. He invited me to come sit on the couch. He said it was one of his best shows, because we sang, we laughed, and that made it possible for other people to say, "Come on over and sit down," because they found out I had some comedic talent, and I could hold my place with whoever was there.

Q: How about The Mike Douglas Show?

A: Mike was another person who tore down barriers — he and I talked in the dressing room one day when I was there to sing, and we laughed and I told him a few jokes and we had a good time. And he invited me back to be a cohost.

Q: The Della Reese Show ran from 1969 to '70. How did it come about?

A: The man who was directing Mike Douglas's show, Woody Fraser, left [his job]. I was working in Chicago in a nightclub and he came to see the show. In my show I talk, tell a few jokes and sing. When it was over he came backstage and congratulated me. And he said, "How would you like to do a television show?"

I said, "I'd love it.

He said, "Good, we'll do one."

Three weeks later, he knocked on my door with a director and set designer and he said, "Are you ready to do the show?"

I said, "If you're ready, I'm ready."

Q: How did your show end?

A: We had a sixteen-piece orchestra, we had guests that cost money and the money that Woody had allotted was not enough. Every show we were ten to twelve thousand dollars over. Eventually our overruns got to be too much, and they wanted to cut the show down — take out the orchestra, the audience — and I said, "No, I'm not going to do that. If it's time for it to be over, let it be over."

Q: Do you feel that doing that show helped pave the way for other women in television?

A: I haven't made the money that other people made, but I've been blessed that I opened doors so people could get in. I'm very thankful for that.

Q: Johnny Carson approached you about being a guest host on The Tonight Show.

A: Yes. I was doing my show and bless him, he loved his audience. He wanted somebody that he felt would entertain his audience. So he started selecting people, and I was working in the same studio he was, in Burbank. And one day, we passed each other in the hallway and he said, "How'd you like to try out hosting?" I said, "I'd love it." I think I was the first woman to do that.

Q: In October of 1980, you were taping a song for The Tonight Show and suffered a brain aneurysm.

A: The aneurysm ruptured and I said, "Into your hands, I commit my spirit," and I was out. They took me to the hospital, looked at me and decided that it must be something about my size that made it happen. They took my vital signs and they were all good, so they didn't know what was wrong.

They sent me to another hospital — and I was Black and an entertainer — and they decided that it must be an overdose. So they started looking for drugs in my system, and there weren't any. I wasn't too fat and I wasn't a junkie, so now nobody knew what was wrong with me.

My son is a psychiatrist. He sent for my physician, who came immediately, and he said to them, "I see her three times a year, she's not on drugs and that's the size she is — there must be something else we should be looking for." That night, they discovered that the aneurysm had ruptured, and the next morning they sent me to another hospital that had the necessary equipment. I had brain surgery — twice in ten days — and ten days after that, I was doing a commercial for Campbell's Soup.

Q: Eddie Murphy wound up being responsible for the 1991–92 CBS sitcom that you would do with Redd Foxx, The Royal Family.

A: It came by so simply. We were doing [the film] Harlem Nights [starring Murphy and Richard Pryor] and we were at this long table, and this young lady who was the prop master would come and pass out fruit. This particular time, Redd says, "Where's my orange?"

And I said, "She's on her way with the orange."

"What is her name?" I said, "Renita."

He said, "Renuzit, bring me the orange!"

I said, "Her name is not Renuzit; her name is Renita."

He said, "Renita, Renuzit, what difference does it make?"

And I said, "Chartreuse, salmon, pink, yellow — what difference does it make when your name is Redd?"

Redd rises, "Arrr!" And everybody standing around is cracking up because this is all extemporaneous, and we are going at each other — we're friends, so we can do this. Eddie just slides down the wall, laughing. He said, "Let's take a lunch break," and he went in the trailer and wrote The Royal Family. When it was ready, he handed me my part and he handed Redd his part.

Q: There was behind-the-scenes tension between Redd and one of the producers on that show?

A: This man wanted to present himself like, "Some of my best friends are Black. I know a lot about Black people, and I've been with Black people all my life," which is very offensive. And he was always trying to tell Redd how to be funny. So that friction ran between them.

One day, Entertainment Tonight came to interview Redd, and he's in a room with them. We're rehearsing a scene, and all Redd had to do was walk behind my chair, so they sent someone else to do that. And this man says, "Where is Redd?"

I said, "He's having an interview with Entertainment Tonight. He doesn't have any lines here; he just has to walk."

"If he's supposed to walk past, he should be here to walk past."

So he goes in, stops their shooting and brings Redd out. When Redd finds out all he has to do is walk across the back of this scene, that anybody could have done that, he becomes livid and he falls. He was always doing pratfalls, and I thought that's what he was doing — everybody did. He was laying on the floor, and I leaned down and put my hands on him. He said, "Get my wife, get my wife."

I said, "Somebody get paramedics, and somebody go get Mrs. Foxx."

They went and got her. They pronounced him dead, and they put him in the ambulance, and we all followed him to the hospital. Then he came back and stayed alive for four and a half hours. We're all sitting in the lobby of the hospital and the doctor comes out and says, "Mrs. Foxx, we've done all that we can do. Your husband is gone."

Standing this close were two of the producers, and they said, "What are we going to do with the script? This script was written for Redd and Della. Who's going to replace —"

Mrs. Foxx is sitting right here. They just told her that her husband was dead. And I went crazy. I went absolutely insane. Got in my car and left, and I made up my mind on the way home that I wasn't ever going to do television that way again, because if something happened to me and they treated my husband and my daughter that way, I'd have to come back. And once I go, I don't want to come back.

Q: Touched by an Angel started in 1994. How were you approached about doing the pilot?

A: My husband gives me a honeymoon every year. William Morris called me and offered me this part. I said, "I can't take it because it's time for my honeymoon."

And he says, "Have you ever been to Carolina? It's a wonderful place," and then he quoted me this salary amount. And he said, "You don't have to carry the show — you only have a couple of days' work, and there will be plenty of time for your honeymoon," and he quoted me this price again, which was really nice.

I told my husband everything the man told me, and he said, "If you wanna go to Carolina, it's all right with me." So I went and we made this pilot. CBS hated it. It really was horrible. I said to my husband, "I don't want to do this because I'm back in the same situation I was in with Redd, and I promised God and two other people that I'm never going to do this again."

"Well," my husband said, "I don't know, babe, I got a feeling about this and I think you oughta talk to God."

So I came home and I said to the Father, "You know how I feel about this. I appreciate that you put this in my path, but I'd rather you give me something else." And as clearly as you hear me speaking to you, the voice said to me, "Do this for me." At the time, I thought I was smarter than God, so I tried to break it down so he would understand. I prayed anew. I sat there, and when I started to listen with my spirit, the voice repeated, "Do this for me and you can retire, if you want to, in ten years."

Q: And did you believe that?

A: I did it for nine years.

Q: What do you think was the turning point for the show, going from nearly being cancelled at one point to being a top series?

A: People need something to help them with their lives. In the show, we didn't tell you what to do — we said, "Did you ever think about it like this?" If you were distraught or at a place where you felt there was nothing else to do, we would make a suggestion. "It doesn't have to be that way — you can change your mind and change your life." It gave people, in the privacy of their homes, a chance to know that they, too, could change their minds and change their lives.

Q: In October of 1997, you held a news conference about a salary dispute that you had with CBS.

A: They wanted to give everybody else a raise, and they didn't want to give me a raise, and I couldn't accept that. Just that simple.

Q: And how was that settled?

A: They gave me my money.

Q: How do you feel about your life and career now? How important is it for you to keep working?

A: I need to work. I get bored too quickly. So I'm pastoring a church, I'm writing. I'm at a wonderful place. I can still do whatever I want to, but I don't have to do anything anymore. I'm not talking about money. I made my bones, I got my trophies, I put my work on the line, people accepted it. So, if I wanna do something, I can. If I don't, I don't have to, and I love it.

The contributing editor for Foundation Interviews is Adrienne Faillace.

Since 1997, the Television Academy Foundation has conducted over 900 one-of-a-kind, longform interviews with industry pioneers and changemakers across multiple professions. The Foundation invites you to make a gift to the Interviews Preservation Fund to help preserve this invaluable resource for generations to come. To learn more, please contact Amani Roland, chief advancement officer, at roland@televisionacademy.com or (818) 754-2829.

To see the entire interview, go to: TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #4, 2023.