His parents didn't want him to be an actor. So at college, Charles Floyd Johnson studied acting for kicks while earning a bachelor's in political science and history, and then a law degree. But the acting bug stuck with him, prompting a cross-country move to Hollywood when he was in his late twenties. And though he did find work as an actor in television, it was as a producer of popular broadcast network shows that Johnson achieved his greatest success.

Hard work and people skills form the core of his award-winning formula. "When you work on shows like I've been on for long periods — seventeen years on NCIS, nine years on JAG, six years on Rockford and Magnum, P.I. — you create families," he said last year. "To be successful and to have long runs, there has to be synergy." That synergy resulted in Johnson being nominated for four Emmys: two for Rockford and two for Magnum. He and his fellow producers took the win in 1978 when The Rockford Files was named outstanding drama series.

Johnson, a Vietnam-era military veteran, also worked in film. He produced 2015's John Lewis: Get in the Way, the first documentary about the civil rights leader and congressman, as well as Red Tails, a 2012 film about the Tuskegee Airmen, the pioneering African-American pilots and airmen of World War II. A member of the Producers Guild of America, Johnson founded and produced that organization's Oscar Micheaux Awards, the forerunner of the PGA's Celebration of Diversity Awards.

Johnson was interviewed in March 2020 by Adrienne Faillace for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire interview can be seen at TelevisionAcademy. com/Interviews.

Q: As a child, did you know what you wanted to be when you grew up?

A: I always wanted to be in the entertainment industry. We had one movie theater in our town [Middletown, Delaware]. It was segregated. I had to sit with the other African Americans — at that time we were probably "colored" or "Negro" — in the balcony on one side of the theater. Sidney Poitier had just made his debut in films like Blackboard Jungle, and there was a film with Dorothy Dandridge called Carmen Jones. I remember watching and going, "I want to do what they do."

Q: Did you pursue that at college?

A: I did. At Howard [University], the first thing I did was seek out the theater department. But my parents didn't want me to be in the entertainment business. So I ended up with a major in political science and history, and a minor in education. But I did lots of plays in college; I was in the Howard Players.

I went on to law school at Howard and became a member of the Law Journal. I graduated fifth in my class. Then the Vietnam War started, and orders came for me to go into the military.

Q: Did you go to Vietnam?

A: No — I almost did. I had taken the bar, but I hadn't gotten the results yet. I went to basic training and then was sent to Fort Dix, New Jersey, to work for the Staff Judge Advocate in the army.

When I got out of the military, I went to work in Washington, D.C., as a lawyer for the government. During those three years, I spent my evenings and weekends in theater — I did a lot of community plays and local television.

I was about twenty-eight, I made a decision. I thought, "I don't want to be thirty years old and doing this. I want to be doing what I really want to do." So I found a school in Los Angeles called Professional Theatre Workshop. Because I had been in the military, I had the G.I. Bill, and they accepted it. So I applied, got in and went to California.

Q: How did you find life in L.A.?

A: I didn't know anybody. I found a little apartment in Hollywood near the school, and I went to class four days a week. You had to get pictures and a résumé together and try to find an agent. I did that for about ten months, but I was running out of money. I was telling a friend, Connie Bryant Milton, that I needed a job and she said that her husband, Richard Milton, had just gotten out of the mailroom at Universal Studios and into the business affairs department.

He got me a chance to interview for the mailroom. They didn't want to hire me because I had a law degree. They said, "You're going to be in here five minutes and then gone." I harangued them, and eventually a place opened up. But I was only in the mailroom for three days before a slot opened for me in business affairs.

Q: What did you do there?

A: I was a production coordinator. We were assigned to different shows to work on clearances, look for problems in the dailies, find directors and writers, do the contracts.... It was a great learning experience.

I got assigned to The Rockford Files. Roy Huggins was then the executive producer, along with Meta Rosenberg. And I had worked [as an actor] on Toma, which was Roy Huggins' show. One of the people under Roy on Toma was Stephen J. Cannell. Stephen was already a shining star as a writer on Universal's lot. And he got assigned to write the pilot for Rockford.

Then Roy left, and so did a couple of the producers. The phone rang one day, and it was Meta and Steve. They were now running the show and they said, "How would you like to be our associate producer?"

Well, I had still been pursuing acting on the side. But you weren't allowed to act and work in production — the Screen Actors Guild and the studios didn't allow it. I'd had a couple of roles on Toma; I did a Six Million Dollar Man; I did a Kojak. I thought, "You can probably always act, but you're not going to be offered a chance to be an associate producer every day." So I took the job.

There were almost no associate producers of color on the lot. Later on, a couple of others joined me. But it was a trailblazing position, and I learned on the job.

Q: What was it like working with Stephen?

A: He not only became my boss — he was my mentor, my friend. I wanted to become more creative in the producing area, so he encouraged me to write. It was on Rockford that I got into the Writers Guild, and that helped my profile.

David Chase [future creator of The Sopranos] came on as the story editor, and he was so good that after two years they moved him up to producer. But Meta and Steve decided they didn't want to make David a producer without making me a producer. So David and I became producers at the same time. We were all together for almost six seasons on that show. Eventually Juanita Bartlett became one of the producers, as well. I couldn't have had better supporters and colleagues.

I became a producer in '76, and in '78 we won the Emmy for Outstanding Drama Series. That was really something.

Q: You stayed at Universal for a while, didn't you?

A: Yes. I ended up working on a few movies-of-the-week before I went over to Warner Bros. on Bret Maverick.

This is where life became very serendipitous. One of the assistants on Magnum, P.I. had been my first assistant on The Rockford Files, and she said to [producer] Don Bellisario, "You should get Charles Johnson on the show."

The phone rang and Don asked, "Has Universal called you about coming to work on Magnum?" I said no. He said: "Well, I want you on my show."

Don was a wonderful creator, but he was a tough producer to work with. I was a little nervous because several people had gone on that show but didn't last. So when he called me I said, "I'm happy to come work, but I don't want to get fired shortly after coming over. Maybe I should just come on as a consultant."

He said, "No, I want you on as a producer," so we worked it out.

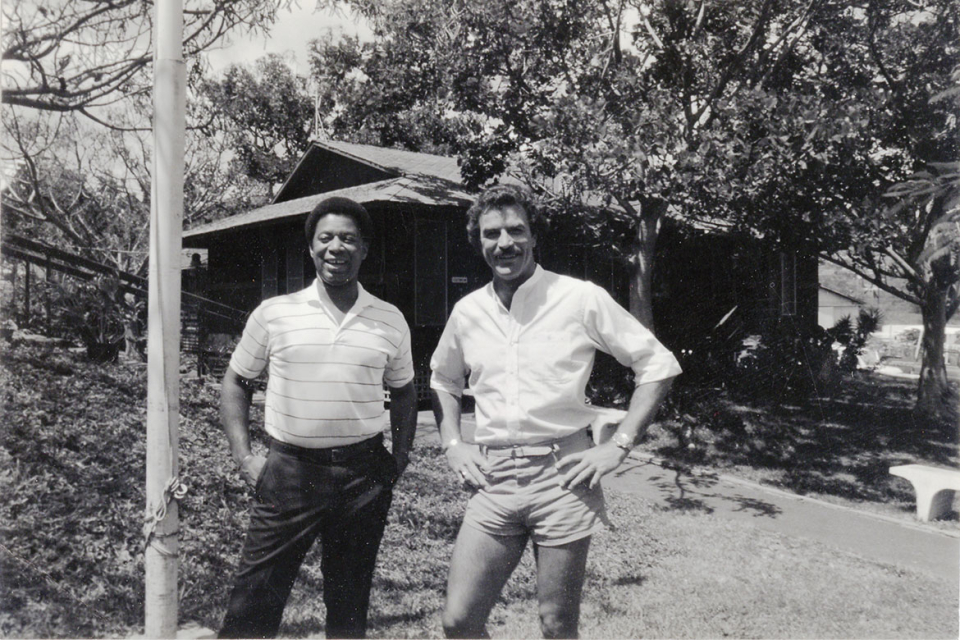

The company was shooting in Honolulu, and I was going to be the producer in L.A. But about three months in, they said, "You should go to Hawaii." So I went. I was there for six years of the eight-year run.

Q: Before we leave Magnum, can we talk about the finale and the identity of Robin Masters? That was left unexplained....

A: Yes, it was.

Q: Was Higgins (John Hillerman) really Robin Masters, the unseen owner of the Hawaiian estate?

A: We left it up in the air. We decided to leave it as whatever you want to think. I personally think he was not. I think there was an actual Robin Masters. And I loved the fact that Don got Orson Welles to do the voice of Robin Masters. But it was just one of those things. David Chase did something like that on the finale of The Sopranos, where you just don't answer all the questions.

Q: You next joined Quantum Leap....

A: Yes, in '93.... NBC had picked Quantum Leap up for its fourth season, but there were budget problems. I loved doing that show. It was so interesting. Every week was a stand-alone — it was a hard show to do.

Q: Is that part of what you enjoy about producing? Problem solving and rising to challenges?

A: Producing really is a craft. To be good at it, you've got to be very attentive to people and problems.

I've been a hard worker. I started in the business in 1971, and I'm almost hitting the fifty-year mark. And I'm a people person. I get along with them. I know how to motivate them.

I like people. I listen.

I used to think sometimes that the sign on my door should be "The Doctor Is In." Because there's a lot of that. When you work on shows like I've been on for long periods — seventeen years on NCIS, nine years on JAG, six years on Rockford and Magnum — you create families. You spend more time with those people than with your own family.

To be successful and to have long runs, there has to be synergy. And you have to be good at spotting talent and putting the right talent in the right places — in front of the camera and behind the camera. You're only as good as the people you surround yourself with.

Q: How did you come to work on JAG?

A: JAG was on NBC in its first season, but it got canceled and picked up by CBS, where it became a very different show. Les Moonves [then president of CBS Entertainment] wanted to make it more of a legal drama — the show rarely went into a courtroom, even though it was called JAG [Judge Advocate General].

The interesting thing about doing the show was, when I was in the military, I was in the Courts and Boards Division — part of the Staff Judge Advocate, which is the U.S. Army's counterpart to Navy's Judge Advocate General. I ran that office. So when they called me to do JAG and wanted to change it into more of a legal show, I knew what running a daily office looked like.

The first year, they didn't have a permanent courtroom. They didn't have permanent offices and they had no permanent sets. After all my years on shows like Rockford and Magnum, I knew that's how you could save money. We got the production designer going, and that's how we transformed that show.

Q: You also had an on-camera role as a toxicologist....

A: That was great. One of our producers, Stephen Zito, knew I'd done some acting. He came to me and said, "You should work on this show." He created this character of Dr. Bruce Gasden, and it was not going to recur. But in the very first episode, we had Trisha Yearwood on the show playing a forensic scientist and Gasden worked with her in the lab. Trisha ended up recurring in three or four shows, so every time Trisha would come, they would bring Bruce back.

Q: NCIS spun off from JAG in 2003 and is still on the air. How exactly did it start?

A: When we were finishing JAG, everybody used to say to Don, "You need to spin this off into something else." So Don created NCIS out of a JAG episode. That became a two-hour episode with Mark Harmon. It was going to be Law & Order in the military. The first hour was the investigative portion of the show, and the second hour ended up in the courtroom. That was going to be the model. However, when they tested it, the first hour tested so strongly with Harmon as the investigator that CBS decided to just do the investigative portion. It became NCIS.

Q: What led you to executive-producing the documentary John Lewis: Get in the Way?

A: One of my dear friends, Donna Guillaume, was friendly with Kathleen Dowdey, who was working on a John Lewis documentary. She had done some filming of him and the people around him, but she couldn't get it going. Donna called me and said, "You're the one who should do this."

I told her, "Donna, I've got so many things to do, I just can't."

And she said, "But it's John Lewis, and nobody's ever done a documentary on John Lewis. Can you believe that?"

So I agreed to meet with Kathleen. She and I talked, and I thought, "This man has been a warrior for justice for all these years, starting when he was eighteen. He has been there for the common man." So I joined her and helped to raise funds, to put a crew and the film together. Eventually we were able to get people like Norman Lear to help us, and we got it on PBS. But the amazing thing was getting to know John Lewis. He's a gentle man, trying to make life better for everybody. [Lewis died on July 17, 2020.]

We put it in film festivals, and the first one was at Washington University in St. Louis. We invited John Lewis — he hadn't seen it yet. At the screening, I sat behind him and I got to watch him as he watched it. He was very impressed with the film. That is one of the most gratifying things I've ever done.

Q: You've noted that you were one of only a few African Americans in the industry when you started. What changes have you seen?

A: Back when I was working as a production coordinator, Universal was getting ready to do a feature. They called me and said, "We need a Black director to do this film. Can you make a list?" I made a list of maybe twenty-five people who were out there directing. One of them did get the movie.

Today I couldn't make a list of directors, because there are maybe 500. That's a good thing. There's more opportunity out there than there ever was. The growth has been enormous. I may be the first African American to have worked on a nighttime drama as a producer. I've never been able to verify that, but I think I might be.

We still have the racism problem — it's always there. It's in every aspect of our lives. African Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans, Latinx... all feel like we get less. And women have to fight very hard.

It was a white male business for a long while, but there's much more opportunity now. I'm thrilled to see that. But what you find in our industry, I call it the diversity dance. I don't think we'll ever beat the problem, at least not in my lifetime. It'll always be difficult.

Q: How did you deal with challenges you faced along the way?

A: I had a friend I worked with who I don't think had worked with a lot of African Americans. Every time I would come around — this was very early in my career — he'd say, "Oh! It's Charlie Johnson. We'll let one of your kind on the elevator," or something like that. Always a racial reference.

I don't think he was doing it to be mean. One day I got in the elevator, and he made a joke about race and I stopped. There were about eight people in the elevator. I said, "Why do you always refer to me — every time we're in company like this — in terms of race?"

And he said, "I'm just joking with you. You're too sensitive."

I said, "I don't find it funny, and I don't find it very nice. So don't do it." I said that to him in front of everybody on the elevator. He never did it again.

We became great friends. He's gone now, but years later he said to me, "I learned a lot when you did that." As for me, I learned to protect myself and to not let people take advantage. That's a defensive posture you learn to adopt as you move forward.

Q: What is your proudest career achievement?

A: I've done three projects in my career that have to do with color. One was a show I did many years ago [for public station KCET] called Voices of Our People... in Celebration of Black Poetry. I got to produce it, as well as perform in that.

Then I got to do Red Tails, about the Tuskegee Airmen, with George Lucas [as the executive producer]. That was amazing because I traveled the country, interviewing the airmen and putting the history together and working with Lucas. And then I worked on the documentary about the amazing John Lewis.

Those are the things most dear to my heart. But I'm also proud of the broadcast shows I got to work on — and the variety of them. I picked out the three shows that had to do with color because all the other shows I worked on had nothing to do with color.

And that was interesting — to do all of those shows and to sometimes be the only producer on the show who was of color. I was very proud of that — to be able to do my job

well, and for so long.

To see the entire interview, go to: TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #3, 2021.