In the 1950s, Lee Grant found that most doors in Hollywood were closed to her.

The actress had been swept up in the hysteria surrounding Senator Joseph McCarthy’s hunt for Communist sympathizers. Called to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities during the so-called Red Scare, she refused to name her then-husband, Arnold Manoff, a TV writer and committed communist. She was promptly blacklisted — and barely worked for 12 long years.

In the early ‘60s, as the studios began to once again hire blacklisted writers, producers, directors and actors, Grant was cast on the television drama Peyton Place. For her performance as bad girl Stella Chernak, Grant received an Emmy — the only one for the entire series — in 1966. Not long after, she became one of a few pioneering female directors.

In her just-published autobiography, I Said Yes to Everything: A Memoir (Blue Rider Press), Grant relates with stark candor her promising acting launch, the dark years of 1952–64, and the resurrection of her acting career, followed by 3 successful decades as a director of TV, documentaries and feature films.

New York City born and bred, the Method actress made a splash on Broadway at age 20 playing a 40-something shoplifter in the play Detective Story. She reprised the role on film 2 years later, in 1951, and was nominated for an Oscar while also picking up the best actress award at the Cannes Film Festival.

During the blacklist years, she appeared in some small independent films, episodes of the television soap Search for Tomorrow and on Broadway, which had no blacklist.

After Peyton Place, Grant won a second Emmy, in 1971, for playing a breakaway housewife in the TV movie The Neon Ceiling. Five years later, she took home an Oscar for her performance opposite Warren Beatty in the feature Shampoo.

She had already started to inch into directing when George Schlatter, co-creator of Laugh-In, hired her to co-direct his 1973 comedy special, The Shape of Things, starring Phyllis Diller, Lynn Redgrave, Joan Rivers, Brenda Vaccaro and Grant herself, among others.

It was the start of a new phase of her career. She was one of the first women to take part in the American Film Institute’s Directing Workshop for Women, in 1976, directing a screen adaptation of August Strindberg’s play, The Stronger. After that she turned to documentaries, most of which expressed her strong beliefs about social injustice.

Among the documentaries she directed were The Willmar 8 (1981), about a sex-discrimination strike at a bank, and When Women Kill (1984), about severely battered women. For HBO she directed What Sex Am I? about transgender individuals (1985) and, a year later, Down and Out in America, about poverty during the Reagan presidency, which brought her an Oscar for best documentary feature.

Ever versatile, Grant went on to direct dozens of Intimate Portraits for Lifetime Television between 2000 and 2004.

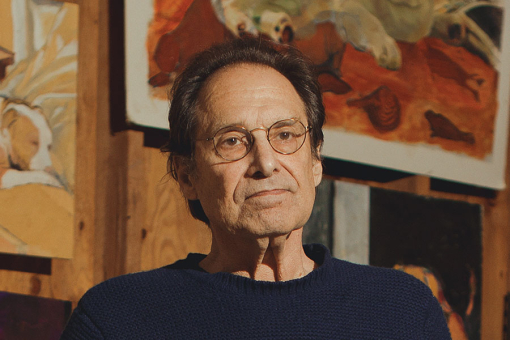

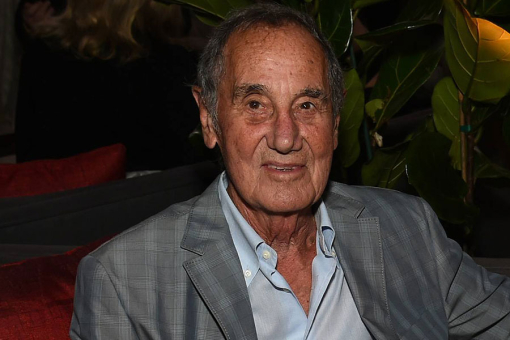

Emmy contributor Jane Wollman Rusoff chatted with Grant (who also spoke at length with the Archive of American Television during an on-camera interview) in her art-bedecked New York City apartment. Public records put the actress at somewhere between 85 and 88 years old, but she’s not telling.

“I’m around that age,” Grant allows, mischievously. “But I don’t want to know the exact number because then, like the Wicked Witch, I could dissolve in a pool right at your feet!”

What were you doing before you were cast in Peyton Place?

I had a huge triumph playing Electra at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater in New York. I had gone into rehearsal for As You Like It when I got a call from my agent. She said she had signed me to Peyton Place — without asking me! I was stunned. I said, “I can’t leave Joe! We’re opening in a week.” He was like a god to me. She said, “You have no money. You can’t support yourself and your child [actress-to-be Dinah Manoff]. You have to do this.” I knew she was right.

Peyton Place was on three nights a week. That must have been challenging.

To me, it was like dinner. It was yum! I couldn’t work enough. My appetite was huge.

So getting the Emmy was icing on the cake?

It was more than that. It was kind of unreal because it was a public affair and so open. I still had my old blacklist fears that somebody would say, “You’re giving this to the wrong person. This is a blacklisted actress.”

You write that your former husband, Arnold Manoff, who died in 1965, was a communist. Were you?

No. They wouldn’t let me in. I was too uneducated. I didn’t know anything. The theory of communism makes sense to me. But if a dictator and a killer take over a theory, what difference does it make?

Did you try to end the blacklist?

I spent a good ten years fighting it. I was committed to get rid of it. That became more important to me than my career, more important than acting. The fight became my life.

You must have been excited, getting all those TV offers as soon as you were taken off the blacklist.

A lot of the guys who were hiring me, who knew I’d been blacklisted, were so great — [producers] Paul Monash, Norman Lear, Bud Yorkin. They went out of their way to work with me because their hearts were in the right place. And I was the only ex-blacklisted young actress around!

In 1975 you starred in your own sitcom, Fay. But NBC took it off the air after only 8 episodes. Still, you were nominated for an Emmy for outstanding lead actress in a comedy series.

It was a lot of fun, but I had no idea that they were going to cancel it. When I showed up for work, the furniture was on the street. I was supposed to be on the Johnny Carson show that night, so I walked across the lot and told him: “You booked me for tonight to sell my show, but now it’s canceled.” He took pity on me. He said: “Come on anyway and talk about being canceled.” So I did.

When you began to direct, did you approach the work with confidence?

With that first show, no. George Schlatter said he wanted me to direct his comedy special, and I said, “What? No!” I had such anxiety. But later I felt confident because I’d been acting for so long and earning my living as an acting teacher during the blacklist.

What did you enjoy about directing documentaries?

For the first time I could say, through what I was filming, what was terrible, what was wrong, what was right. I got to explore all these things and not be worried that somebody was coming to get me.

After you closed the production company that you had with your current husband [of 52 years], producer Joseph Feury, you became a director for hire. How was that?

With my own company, nobody told me what to do. Nobody interfered in my process — not when I did documentaries, not when I was acting, not when I was directing. I’ve seen directors who know how to handle [meddling] well and not let it bother them. They laugh it off. But I was sitting on rage all the time.

You have to be able to hang out, especially if you’re a woman. You have to take it easy and make jokes. You have to not take everything so seriously. I don’t have that [ability] when I work. Producers were picking on things, and I had no patience with them. It drove me crazy.

You were still taking occasional acting roles, like the mother of attorney Roy Cohn in the telefilm Citizen Cohn. He was a blacklist-era villain….

I was asked to play that part or another one. I said, “I want to play Roy Cohn’s mother! I want to be the mother of the alligator!” It was great to get out all the bile that was still inside me from that period — and I got an Emmy nomination for it!

You directed a number of Intimate Portraits installments for Lifetime, in the process interviewing some amazing subjects.

The first one I did was Bella Abzug. Then Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan and Marlo Thomas. These were heavy-hitting women who I couldn’t wait to interview. Although a lot of the celebrities I interviewed were friends, I didn’t really know them until I did these shows. I’d been in living rooms socializing with them forever, but found I didn’t know anything about them.

There were only about 2 or 3 other women directors at the time you started to direct. Were you conscious of that?

When you’re inside the dome, you don’t think of yourself as a “woman director.” All you’re doing is trying to get something on. But I had so many breakthroughs and did so much work that it was a real fun time.

Originally published in Emmy magazine issue no. 06-2014.

Related Features